By Susannah Darling Khan

I was supremely lucky to have an Uncle and Aunt who were some of the first organic farmers of the modern era. Uncle Arthur and Aunty Liz’s small, 35 acre farm was called “Tyllwyd”. From some of the fields you could see the wide stretch of Cardigan Bay, coloured anew each sunset. “Tyllwyd”, which means grey house in Welsh, was an unpainted farm house with a dilapidated outside loo.

Tyllwyd was an oasis to many young people looking for their way. In terms of money Liz and Arthur were poor but, in the soul, they were the richest people I knew. They were interacting with the land, the elements and those beautiful Jersey cows. They were doing what was true and meaningful to them and they were satisfied.

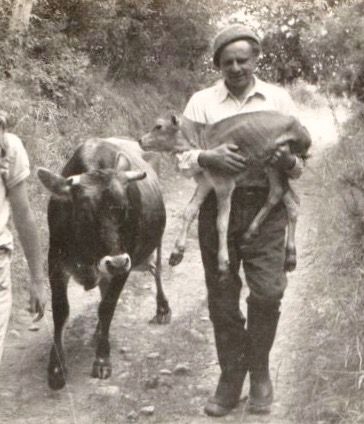

As a child already enraptured with nature, the rich intoxicating smells of earth and hay and cows were enough to keep my soul yearning for more. Each year we would go in the summer to help with the hay harvest and this was my heaven on earth. I loved their small herd of beautiful golden Jersey cows. “Silver Rain” was peaceful, gentle and wise. “Maid Marion”, beautiful and shy, “Razzle Dazzle” huge and wild and a bit frightening. Each of them was tended personally and lovingly as my Uncle attempted to keep his deal with his cows. He had made what I can only call a spiritual agreement with them that, in exchange for their milk, he would look after them well, and keep them long after they were no longer economically viable. They were milked by hand and cared for with natural biodynamic remedies. They kept their natural horns and fierce good looks and, when eventually their life had to end, they were killed cleanly on the farm with no fear, where they would be buried, on the land they had lived on.

In those days there was no premium for organic milk. The Jersey cows gave high butterfat, for which Liz and Arthur got a premium, but “organic” didn’t yet mean anything commercially. So, every day, Tyllwyd’s single churn of the best possible organic hand milked milk would get poured into the vast tank, mixed with all the milk from all the other nearby conventional farms. Uncle Arthur was happy that the consumers were still getting a homeopathic drop of organic, biodynamic goodness in their milk. He prided himself in the knowledge that his milk was the best going into Felun Fach creamery. Indeed it was found to be such at inspection after inspection, not just in terms of its butterfat content, but also in terms of cleanliness (lack of bacteria and dirt) and longevity. So this, as my cousin Jack Darlington said to me last week “was not wasted effort by an eccentric but meaningful work by somebody who knew exactly what he was doing.”

At one point they were totally skint. School uniforms needed to be bought and there was nothing to buy them with. Uncle Arthur was worried. He thought that he might have to break his agreement with the cows. One of them was coming to the end of her life and he knew that if he sold her carcass as dog’s meat rather than bury her on the land as per his promise, he would get £300 for her. He went out to pray in his “church”, a particular fairy ring in a field high up on the farm. He spoke to God and asked for guidance: “I think I am doing what you have asked me to do, but now I am not sure as I am simply not earning enough to live. I do not know any more if I am on the right track. Please send me a sign to guide me and let me know your will.” He was not sure if God had heard him, but the next day a cheque arrived in the post for exactly £300. It was from Anna, a young woman who had sought refuge there at a turning point in her life. She’d suddenly become aware of wanting to say thank you. So the cow stayed on the land, the children had their uniforms and Uncle Arthur had his answer.

Learning to milk was a great joy for me. Silver Rain was the patient, kind teacher cow for beginners such as 8 year old me. Those cups of milk; warm, frothy and direct from her udder were a blessing in my childhood. I feel why cows are sacred in India; their beatific, peaceful and generous nature seems holy to me. I spent many an hour as a child, quiet in the barn, comforted by the calm rhythm of cows eating their hay and chewing the cud.

I would watch my cousins milking, the muscles of their forearms sculpted by long practice. I learnt to milk, and I had enough strength for one cow, but not for the steady stream of them who came to the milking byre every single morning and evening. It’s a job that takes calm, precise, gentle, strong, movements (and incredible commitment – imagine, twice a day EVERY single day of every year) and offers a calm, benevolent peace. It’s rare now for anyone to have this experience of hand milking in the industrialised world. I feel so privileged to have had the opportunity to experience it. Milking is done, almost everywhere now, by machine and it’s a totally different vibe. I learnt how to tuck the milking stool under me, wash the cow’s udder carefully with warm water, absorbing the sweet smell of oats and molasses as the cow licked her bowl clean and then the satisfying singing of the milk rhythmically jetting into the bucket, the cow peacefully chewing the cud.

Just thinking about Arthur brings, I imagine, his voice to life in your memory. That slightly nasal, powerful brummy twang, salted with laughter, of the earth mixed with tractor grease and the sweet smells of cows and hay. I am comforted and inspired that this man walked the earth, and that I had a chance to walk in his footsteps. He was brilliant, bothersome, wonderful and frustrating, powerful and tender. Liz, I bow to you, and the way you shared, so passionately, his commitment and lived to tell the tale. As my mother once said, Arthur might have been a better farmer if he hadn’t been so busy talking about politics all day. However, another way of viewing it is that his farming was politics of the deepest level. It was his commitment to service, to life on earth, to the future and to the well-being of the people. And when you looked at his cows, you could see the true commitment and accomplishment he had as a farmer. His cows bloomed.

I am blessed to have had this unusual heritage and experience that is rare in our world these days. I am very grateful to Arthur and Liz. I have thought that they might be surprised to know how often I refer to their teachings in my teachings.

Now Uncle Arthur is 92 and is slowly, gently fading. His body is weak, but he is totally there. I was touched and sad and happy to be able to visit him and my Aunty Liz in August with my father (his younger brother) to say thank you once more. Meeting Jack, my cousin, we found we shared so much about land and humanity. When I read him this piece, I thought he might say I was romanticizing Tyllwyd and his parents and all they stood for. Jack knew what it meant to get up on dark freezing cold morning after dark freezing cold morning to help milk the cows before going to school. But he said that this writing was accurate and added those important words (above) about Arthur’s conscious meaningful work. He also said that Arthur had taught him to honour and relish physical labour. I love that being spoken and I feel that too. I had never put this together for myself, how I grew up involved with school and book learning, but also needing to work physically on the land to express something else. That was that!

My father is making a booklet of people’s memories of Arthur and, when I sent him this piece, he asked whether I had sent it to Liz and Arthur. They don’t do computers, so I printed it out big for Arthur, as his sight is better than his hearing. Liz held up the pages and said he read them all avidly. When he had finished, he said a quiet, happy “YES” and sank down to rest contentedly. I am so glad to have been able to communicate this detail to him now.

With love and gratitude, Susannah Darling Khan