By Susannah DK and Dick S. Darlington

Some time again my father gave me this piece of writing from my grandfather, his father: Dick Samuel Darlington, who died before I was born. Meeting him in this piece of writing about an experience he had in the First World War has been strong for me, and I’d like to share it with you. I feel proud to have him at my back. His words speak for themselves.

With love and gratitude for all our grandparents, and for everyone who has come through war with any of their humanity intact,

Susannah DK

A Soldier’s Tale

Guts or Fear: Which?

During the war (1914-1918) I had some pretty wonderful experiences. Religious is the only way I can describe them; though I am a bit shaky on that point because these experiences did not prevent me from becoming more and more doubtful about the aims and methods of the war. I had already arrived, not by reasoning or anything conscious like that, but by a kind of instinctive feeling that all war was contrary to the will of God, when a friend of mine in the Orderly Room told me that my name was first on the list for the next job.

During the war (1914-1918) I had some pretty wonderful experiences. Religious is the only way I can describe them; though I am a bit shaky on that point because these experiences did not prevent me from becoming more and more doubtful about the aims and methods of the war. I had already arrived, not by reasoning or anything conscious like that, but by a kind of instinctive feeling that all war was contrary to the will of God, when a friend of mine in the Orderly Room told me that my name was first on the list for the next job.

This was not news to make one jump for joy. That the senior officers were confident I could be trusted to see a job through, and that a junior officer was to be sent with me to give him some experience of this kind of thing, (so my friend informed me confidentially) was a compliment lost on me. I don’t know that I would have felt any better about it, if I had still believed the war to be worthwhile. All I know is that I was fed up.

Well, the job came along. Or rather, we came along and reached the job. It was to make a breach in a temporary bridge which the enemy had thrown across the river which divided us. The exact military advantage of this need not concern you now any more than it concerned us then. To us it was a job. Normally it meant no more than that. But for me there was now entering the new factor which I have since learnt is described as ‘ethical’, but which to me then, was just one big inner question mark.

If I had gone to my Commanding Officer and told him that I had suddenly decided all war was wrong and I could no longer take part in it, it would have looked very much like funk. If he had asked me whether I knew I was next on the list, I could not have given any answer but ‘yes’; and then of course he would have looked at me with his keen, penetrating though sympathetic eyes, and implied without saying it, “that explains it”. As it was, he sent for me and explained the job as man to man. There was never anything sloppy or sentimental about him, yet he had a way of talking off parade that made you feel that you were his son, and he was full of concern for you. I simply could not have said I was not going to do this job.

But I was shaken to my depths. The way the O.C. had put his hand on my shoulder was nearly a goodbye. I have often wondered since what inner tortures he went through. Then, I was interested far more in myself. I felt the end was near and the deference I received from other quarters did not cheer me.

Was I afraid? Yes and no: fear is a queer mixture of more elementary reactions. There are thoughts of fear and there are bodily reactions - ‘reflexes’ I think they are called. We think we see fear in its simplicity at the exact moment of flight from danger. But there was no question of my running away. I think I was simply miserable. There were so many things I wanted to do with my life, so many experiences I had heard about from other fellows that I had never enjoyed. I had only been a schoolboy before this – and, I was going to throw it away in blowing up a bridge, in a war I no longer believed to be right. Miserable: is there any word in any language of fuller meaning capable of describing the depth of my misery?

People who fly to their Bibles in the hour of crisis, and open them anywhere by chance expecting thereby a divine message are now old-fashioned. I had never been of that variety. Throughout my military training I had read my small pocket Bible regularly. On this miserable day when I sat down to read it, I was so out of joint, so sick at heart, that in sheer hopelessness I let it fall open on my knees, and stared in front of myself, lost to the world. Then my eyes dropped to the Book, and I read “Fear not them that can kill the body only…”. I looked again. It was true. “… and after that can do nothing more”.

Whenever I have looked at these words since, I have wondered that they should have meant so much to me then. My heart became as light as a feather. I was on top of the world; yes, above it, beyond its control. I closed the Book, put it in my pocket, rose and joined a few companions with a cheerful smile.

I heard afterwards that one of them had said I’d got guts. And anyhow no-one could say I was afraid. How stupidly we talk of this subject of fear and bravery, for there is no real difference. I was still afraid, still didn’t want to die, and had still the same doubt about the rightness of what I was doing, but I had in that flash of the eye across the printed page, received into myself a support which was completely outside my understanding, except that I knew it was there. Ask me now what it was and I do not know; but then I believed it was Christ himself at my side. And although now I scarcely believe anything, I still feel that in a similar crisis I would be glad to believe it all again.

But what happened? I must apologise. Naturally you are not interested in my religious beliefs and disbeliefs. Did I blow up the bridge? I will tell you as simply as I can, but you must remember that however bravely I talk, or seem to, I was all the time terribly frightened, that is, in myself. My body including my tongue seemed to be in charge of another being. I saw myself doing and heard myself saying things as if I were a separate person.

The officer selected to accompany me was known to us as Billy. He had a name which rhymed with billycan. To avoid trouble let us call him Lieutenant X when necessary. Well, if I had had the ‘wind up’ as we called it, he had certainly got the double dose.

Our job was to go through a small wood and then scramble down a steep river bank, mostly on our stomachs, to the water’s edge. Thence we were to work our way a bit at a time to the bridge. It was a suicidal business. Darkish night, true, but we seemed to be completely exposed. Terrifying, yet now as I look back, I could almost say I enjoyed it.

It is curious how I dealt with that officer. I don’t know what possessed me. There was certainly no preconceived plan for putting him on his mettle and making him more co-operative. It was when we were beginning the almost vertical scramble down. I looked behind, and there he was with his revolver in his hand coming after me.

“Put that damn’d thing away”, I commanded.

“It’s orders” he stammered.

“To shoot me if I don’t go forward,” I said sarcastically. “Well, I am not going in front with that thing held behind me. You haven’t got proper control of it”.

He nearly blubbered. I was sorry for him – no, no, I can’t claim that – it all happened too quickly for that. I said sharply “I know you are here to protect me, but I don’t want to get shot before I have done this job. Just put that toy away and let us concentrate on the real thing”. He obeyed. And we crawled virtually unarmed to the scene of demolition. I went into the water and fastened the wad of explosive to two piles as calmly as if it had been a demonstration job at home. That was all there was to it. How uninteresting it seems now. Then, there was an intensity in every movement which was almost painful, and yet in retrospect enjoyable. My officer had quite recovered his nerve, and when I rejoined him on the bank, we both knew we were friends for life.

His hand slammed down the plunger, and instantly the quiet night split vertically and sideways. Machine gun fire broke out from all directions. I suppose all the gunners up and down the river on both sides, waiting tensely for a crisis that never came, suddenly gave way to fright when a section of the bridge on our side unexpectedly fell over sideways and sent a dozen or so spars hurtling into the sky.

My officer and I were at peace in all this. We sat hidden from the opposite bank behind some shrubs not bothering that they were not bullet-proof. We were waiting for an opportunity to get up the bank.

“You ought to get an M. C. for that, sir” I said.

“Good Lord, you did it.

“No. Forget me – I feel rather guilty – I hadn’t the courage to refuse to do it.”

“Great Scott! Courage? I never saw anyone with more” he said with real sincerity.

“No sir. You misunderstand me. I did not do anything. Christ took charge of me – oh no – I don’t mean He blew up the bridge – of course we did that.”

“By Jove, we did.”

“What I mean, sir, is that I was in a real jam and Christ took me in hand. I think he protected both us all through, and He arranged there was no-one going over the bridge when you detonated it.”

“You are a bit overwrought,” he said authoritatively, taking charge for the first time. It was extremely odd how he then used scripture, I think without knowing it, as a simple order. I shall never forget it. “Arise, let us be going” he said. And we went.

Was Christ really with me, you ask. I don’t know. As I have said before, I believed it then, and in any case I did have a real spiritual experience, as real as anything else in my life. And my officer and I did have a sense of unity and peace as we clambered back to safety.

But, no doubt, you are right to question my way of putting things. You are right, of course, Christ could not countenance war. That is really common knowledge. But there was another thing which shook me afterwards and still makes me think.

In my elation, I forgot all about another officer and little Frankie – I’d known his people way back at home for years – lying in support, who would have had to do the job if we had failed. That officer was wounded and Frankie got his packet. Of course, we knew nothing about this till later. Yet in spite of my spiritual experience – and this shocks me – I had no glimpse of the truth about Frankie. Of course, like everyone else, I was sorry. He was such a genuine sort.

It was years after, when his mother gave me some of his letters to read that I was, as it were, hit right in the stomach. He too had begun to doubt whether as a Christian he could any longer take part in the war. It was the bridge crisis which had brought him to a decision. But he had had the courage to go to the O. C. and explain his point of view. The old man had persuaded him to put off a decision temporarily, telling him he was only going into support Lieutenant X and me, and there was not much doubt we would manage it by ourselves. Call it funking it, if you like. I respect Frankie’s memory. He had the courage to expose his innermost self to his commanding officer. I hadn’t the guts for that.

Frankie had written in his last letter, “Mam, I would rather be killed than kill.” When I handed the letter back, his mother said something I have never understood. It puzzles and even hurts me. “Now I have seen you,” she said, “I am happy at last. He thought the world of you. He was too kind to want to hurt anyone.”

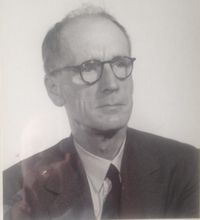

By Sapper Samuel (knowns as Dick) Darlington, 7503, 5th Field Company (Royal Anglesey) R.E.

Dick Darlington returned from the 1st World War, and married Nell Wilkes. They had three boys:

Deryk, who became a neuron-surgeon and then lecturer at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham.

Arthur, who, with his wife Liz, became one of the first organic farmers in this modern era. Their smallholding in Wales, was my heaven on earth in my childhood.

And my own father, Richard Darlington, whose ground breaking work with public participation as a local government architect and, in his later years with Emmaus UK, continues to inspire me.

Dick was a conscientious objector (CO) in World War II and Dick and Nell’s home became a refuge for COs waiting prison and for shell shocked soldiers.

In honour: Dick Darlington born 29 April 1896, died 24 October 1961.